Personal research website | Google Scholar profile

Feel free to contact Allie at allie128 @ berkeley. edu if you have questions or comments regarding the content here.

According to any extrinsic metric of academic success, Allie is sailing toward completing a highly successful PhD. Allie received a prestigious NSF fellowship for her graduate work, has been honored with numerous teaching and research awards, and will have contributed to at least a dozen publications during her time at UC Berkeley. However, what is most meaningful to me is not these external metrics of success but the grounded balance that Allie has cultivated during graduate school. She is equally at home tromping through tropical jungles, pipetting in the wet lab, coding to solve bioinformatics problems, and discussing big-picture conservation challenges. She is a thoughtful collaborator, and has fostered interaction with researchers around the world. Allie cares deeply about mentoring and issues of equity and inclusion. She shares her knowledge readily with others, tackle challenges with grace, and is generous with her time and expertise. She also gracefully balances her academic pursuits with a wealth of outside endeavors (rugby, too). Allie has grown into the kind of quiet but strong leader that you want at the helm. Yes, getting a PhD is hard work, but Allie has also sought ease and enjoyment in the process. It’s been a joy to be part of the adventure!

– Bree Rosenblum, associate professor, department of ESPM

About Allie

Allie’s research centers around her core motivation of conserving species in the wild. Ever since her first trip to the tropical rainforests of Equatorial Guinea during a study abroad program, she has had a special interest in amphibians. During her undergraduate education at Drexel University, she spent time studying freshwater turtles and dabbled in paleontology, but once she landed on amphibians there was no turning back. Her work at Berkeley in the Rosenblum lab uses cutting-edge molecular techniques to study a disease that has devastated amphibian populations around the world. She also studies the amphibians of Panama, allowing her to conduct fieldwork in one of her favorite places on the planet. Beyond research, Allie is also passionate about mentorship. At Berkeley, she mentored seven undergraduate students in research techniques and served as a mentor for the Berkeley Connect program. You can read more about one of her Berkeley Connect lessons here. Outside of academia, Allie is an avid rugby player, music lover, and member of the queer community. Allie is excited to continue serving as a mentor to the next generation of conservationists and do everything in her power to ensure a future for amphibian species around the world.

Dissertation title:

Genomic perspectives on the pathogenic chytrid fungus and persisting amphibian hosts

My dissertation research is focused on using molecular tools to advance amphibian conservation and better understand the drivers of amphibian declines. My work is centered around the amphibian chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), which has been linked to catastrophic amphibian declines in many areas of the world. During my time as a PhD student at Berkeley I developed and implemented a new method to genotype Bd from noninvasive skin swab samples. I am also using genomic tools to understand how one critically-endangered amphibian species is recovering after a Bd outbreak in Panama.

I. Developing new molecular methods to genotype noninvasive Bd DNA samples

Swabbing a glass frog. Panamá.

The most common non-invasive method for sampling Bd from natural populations is to swab amphibian skin. As a result, hundreds of thousands of swabs have been collected from amphibians around the world. However, Bd DNA collected via swabs is often low in quality and/or quantity. Working with a team in the Rosenblum lab at UC Berkeley, I developed a custom Bd genotyping assay that uses microfluidic PCR technology to amplify many carefully-selected regions of the Bd genome. This new assay has the power to accurately discriminate among the major Bd clades. I published a paper describing this method in Molecular Ecology Resources (here).

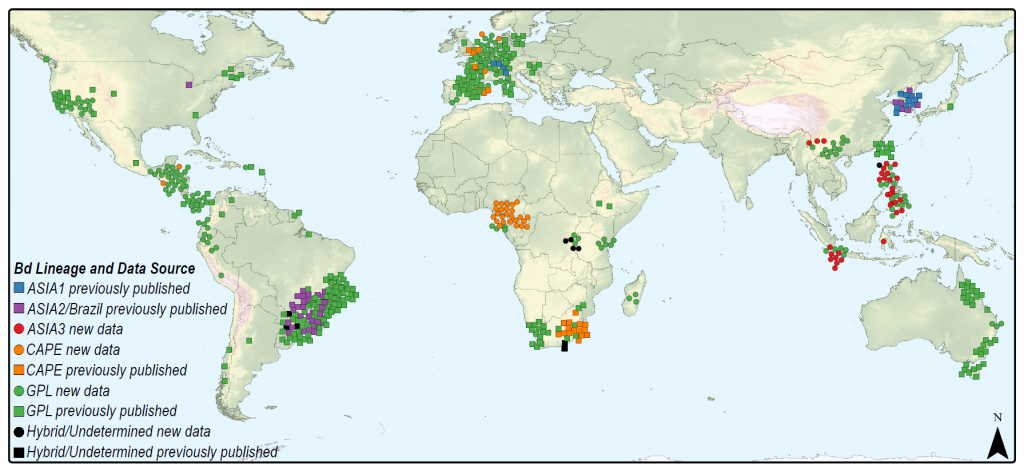

II. Unveiling cryptic diversity of a global pathogen reveals new threats for amphibians

Bd consists of distinct genetic lineages that vary in geographic extent and virulence. Most surveys for Bd report only the presence or absence of the pathogen, but some regions of the world have endemic Bd lineages and simply testing for Bd presence is not very informative. Using the new genotyping method for Bd described above, we can elucidate the historic relationship between amphibian communities and Bd and document recent lineage spread. By forming an opportunistic, collaborative network with amphibian biologists around the world I was able to genotype 222 new Bd samples collected from 24 different countries. This study presents the discovery of a new divergent lineage of Bd called BdASIA3, highlights areas where divergent Bd lineages are coming into secondary contact, and advances our understanding of the global distribution of this pathogen. This dissertation chapter was recently published in PNAS (here). You can also read popular media stories about this research published in Berkeley News, Mongabay, and Daily Nexus.

III. Using whole exome sequencing to understand mechanisms of persistence in the Panamanian Golden Frog

The Panamanian golden frog (Atelopus varius, Atelopus zeteki) declined precipitously in the early 2000’s due to an outbreak of Bd in Panama. Once thought to be extirpated from Panama, A. varius populations have recently been rediscovered in multiple locations across their historic range. Using tissue samples collected from A. varius and A. zeteki before and after the Bd outbreak in Panama, I sequenced whole exomes with the goal of describing potential genetic mechanisms of persistence. In my study I document the genetic diversity of contemporary populations in the wild and in captivity and search for genes under positive selection in wild, persistent populations. My research aims to inform conservation and captive management of these species as well as evaluate the potential for evolutionary rescue in imperiled amphibians. I presented this research at the Evolution conference in 2019 (video below).

Future Plans

I have recently been awarded a Smithsonian Postdoctoral Fellowship to continue working with Panamanian Golden Frogs. By partnering with conservation biologists at the Smithsonian National Zoo & Conservation Institute and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, I will broaden my training in conservation science. During my postdoc I will conduct a reintroduction experiment testing a new breeding strategy for Atelopus varius. I plan to test the hypothesis that an increase in gene flow will protect individuals from deadly Bd infections.