CV | ResearchGate | Twitter | LinkedIn

Feel free to contact Laura at lauradev @ berkeley. edu if you have questions or comments regarding the content here.

Laura Lee Dev has zigzagged along a series of paths rarely taken (in succession) through ESPM. She started her doctoral studies in Ecosystems Sciences, moved into an Environmental History slot, and then shifted into Political Ecology when her EH prof Carolyn Merchant retired. Laura excelled in all of these fields, and won a panoply of grants to prove it. Laura also applied components of her interdisciplinary training to conducting reflexive and participatory research among Shipibo forest dwellers and shamans in Peru. She has situated the major changes in shamanic healing practices and in shamans’ communications with plants not only within the contexts of degrading forest ecosystems, but also in the changing contexts and commercialization of ceremonial healing practices. Laura is investigating the powerful rainforest plants brewed together to produce ayahuasca, used for centuries in the Peruvian Amazon. Laura analyses the establishment, development, and deterioration of practices and relationships between humans as well as between humans and plants. Laura’s work illuminates the ways ideas, plants, and power relations imbued in healing relationships between plants and humans have changed in response to both increased “ayahuasca tourism” and the encroachment of extractive practices on forested Shipibo environments. She is looking at cross-sectional change as well as historical changes in the local and broader markets for Shipibo shamans’ services as guides and mediators of the knowledge generated by brewing ayahuasca. In Laura’s fieldwork, she works with a range of differently positioned Shipibo healers – from those living in the encroached-upon forest settlements to those who have either urbanized or become cosmopolitan (and often rich). Thus new socio-natural networks have emerged and changed as the production and consumption of ayahuasca have become global commodities.

Laura’s commitment to understanding and telling these stories has been unwavering despite the difficulties of living and moving through the Amazon in the rainy season, of learning languages, and of devoting precious time in the field to give back to her teachers and other community members. In addition to delving into the complexities of multispecies analysis, Laura has engaged in action research through a multi-dimensional collaborative project with several communities. She is helping Shipibo create a local forest preserve for medicinal plants, seeking markets for the intricate weavings and embroideries of local women, and serves as research coordinator for a Peruvian nonprofit organization, Alianza Arkana. She shows a similar commitment when she teaches ESPM undergraduates or gives talks: her delivery and her interdisciplinarity made her a favorite when she taught Political Ecology with me. As part of her engagement with the burgeoning “Left Coast Political Ecology Network,” Laura also worked with new assistant professors, post-doctoral scholars, graduate students, and senior scholars to establish a new institutional collaboration across California-based and other universities.

On track to file in late May or June, Laura has already begun work on a post-doctoral project for which she was recruited by ERG graduate, UC Merced professor, and well known Political Ecologist, Dr. Tracey Osborne. Her persistence in realizing her dissertation project has been excellent training for this new project—which will also enable Laura to get back to the Amazon. I have learned a lot from Laura, and hope to continue learning if she and Tracey and others at Merced have time to engage with the Left Coast Political Ecology LandLab, located on the forested shores of Strawberry Creek in our soon to be reoccupied Giannini Hall.

– Nancy Peluso, Professor, Society & Environment, Department of ESPM

About Laura.

I am interested in changing relationships between humans and their environments in the face of globalization and global changes. My studies draw from political ecology, science & technology studies (STS), and environmental anthropology. For my dissertation research I used a multispecies ethnography approach to investigate the relations and practices surrounding culturally important medicinal plants associated with ayahuasca, a psychoactive plant mixture, and the challenges and opportunities indigenous communities are faced with regarding the commodification of their plants and rituals. Specifically, I focused on pathways by which plants, rituals, and knowledge associated with the use of ayahuasca travel between the rural Peruvian Amazon and the Global North. I also work with Indigenous communities to develop community-led responses to local environmental concerns. My background is in plant ecology. I have an MS in ecology from Colorado State University where I studied the interactive effects of climate change and grazing on grassland plant communities.

Dissertation title:

Plants & Pathways:

More-than-humans worlds of power, knowledge, and healing

Background

Ayahuasca, a strongly psychoactive and ‘psychedelic’ Amazonian plant mixture, has long been a powerful fascination for outsiders who encounter it. For instance, several Brazilian religions formed around the use of ayahuasca as a sacrament in the early 20th century, including Santo Daime and the União do Vegetal (UDV) (see Labate and Pacheco 2011). In the last decade the healing powers of these plants have become famous globally, and ‘ayahuasca’ has become a buzzword in certain circles. Part of this attention is due to a ‘psychedelic renaissance’ that has been occurring as psychedelics become increasingly popular and accepted in the United States and the Global North more broadly (e.g. Pollan 2018). Stories about ayahuasca have been circulating with growing frequency in mainstream media outlets, often portrayed as a fetishized sensation that is mysterious, powerful, and exotic. It is seen as a means of healing, but also as a psychedelic adventure. This has been in concert with a growing number of foreigners traveling to the Amazon regions and other parts of South America to drink ayahuasca ceremonially as a form of ‘spiritual tourism’ or ‘ayahuasca tourism’. Subsequently these ceremonial forms and the use of ayahuasca have spread throughout the world and have been adapted and hybridized along the way. This phenomenon is what Labate, Cavnar, and Gearin have termed the ‘world ayahuasca diaspora’ (Labate, Cavnar, and Gearin 2017).

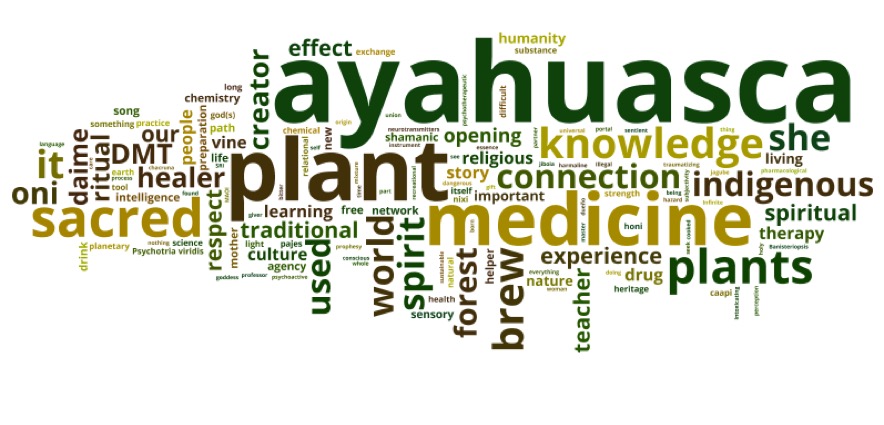

Shipibo healers of the Peruvian Amazon use ayahuasca for cleansing, connecting with the spirit world, and performing healing. The plants used to make it are master plants, which facilitate communication with a suite of other plants that are considered to be important teachers and healers. Ayahuasca is made from two plants: a vine, caapi (Banisteriopsis caapi), and a shrub, chakruna (Psychotria viridis). The term ‘ayahuasca’, a Quechua word, actually refers to the caapi vine. It means vine of death or vine of the dead, which is reportedly because of its ability to open to other worlds beyond the living – what Michael Taussig has called the ‘space of death’ (Taussig 1987). Ayahuasca is generally taken ceremonially at night, and administered by a healer, whose ikaros, a type of ritual song, guide the ceremony and conduct the plant spirits. For Shipibo healers, these plants and plant spirits are lively and animated entities that also participate in and contribute to the performance of the ceremony. However, the meanings and interpretations surrounding ayahuasca have been transformed as healing practices are adapted for Western audiences, and new types of relations among people and plants have emerged. The adoption of Shipibo practices by people from the Global North has consequences for the practices themselves, as well as for the configurations of power through which ayahuasca’s economies and ecologies emerge.

The global popularity of ayahuasca has impacted social, economic, and ecological landscapes in the rural Peruvian Amazon. Ayahuasca tourism in the Amazon has increased notably during the last decade, including along the Ucayali River of Peru and the greater Pucallpa area in general, where I conducted my field research from 2015-2019. This has created a large demand for the plants themselves, indicated by decreasing access to caapi and chakruna in the region. However, ayahuasca tourism has also generated new economic opportunities that are not based on extractive logging, the region’s primary industry, and a contributor to high rates of deforestation. Therefore, ayahuasca tourism may provide rare opportunities for novel land-uses and alternative forms of development.

Meanwhile, the Indigenous groups that originally formed relationships and practices with ayahuasca are often living in poverty, fighting for their territories, and facing systemic racism in their countries after centuries of exploitation and oppression. Providing healing services to foreigners is one way that certain Shipibo families have responded to conditions of capitalism, development, and globalization, and Shipibo healers have now become renowned globally for their use of ayahuasca and other medicinal plants. This has created a greater economic stability, while also increasing the interest in traditional healing practices and medicinal plant use among Shipibo youth. Ayahuasca has been taken up by many Indigenous groups like the Shipibo as a symbolic representation of Amazonian culture, further offering the possibility of economic development and global recognition. However, the extent to which Shipibo communities are able to benefit from ayahuasca tourism has been unclear.

Dissertation Overview and Arguments

My dissertation research has been motivated by four broad and interrelated questions pertaining to the social, economic, and ecological relations around ayahuasca tourism and the global spread of Shipibo healing practices. First, I sought to understand how, if at all, the socioeconomic and socioecological relations around the commodification of ayahuasca differ from those defined by the extraction of other forest resources of the Amazon. Second, I wanted to know whether and how Shipibo communities and healers benefit from ayahuasca tourism, as well as understand the limitations on their ability to benefit. Third, I wanted to understand the consequences of Shipibo healing practices being taken up by outsiders, for the relationships between humans and plants/plant spirits. Lastly, through my own embodied praxis I wanted to reflexively explore how I could work in Shipibo communities and learn from plants as an outsider and researcher in a way that was jakon – a Shipibo word translating to ‘good’, but which literally means ‘toward life’.

In order to address these questions, this dissertation follows two related tendrils, each with their own complex networks of relations, as ayahuasca and Shipibo healing practices are commodified and consumed globally. These two trajectories are neither separate nor linear; indeed, I have found them to be irreconcilably entwined. First, I examine how relationships between plants and humans shift and show that these shifts affect the ability of plants to act in the world. Secondly, I attend to how Shipibo healers and communities interact with ‘outsiders’. At different times, these outsiders have been conquistadors, missionaries, colonists, timber corporations, and tourists. Both of these sets of relations shape material wealth, social power, and concepts of indigeneity. I frame these relations among people, plants, worlds, and ideas, as constituted through practices and mediated by forms of exchange. I examine each of these tendrils at times separately and at others simultaneously through attending to practices performed by both plant spirits and humans (plant-human practices) as they transform through time, space, and cultural milieu.

Following other scholars of the ontological turn (de la Cadena 2015; Kohn 2013; Blaser 2014a), I aim to take Indigenous ontologies seriously. As such, I view the participation of other-than-human entities in Shipibo healing practices as not just symbolic; plant-human relations have real effects on the world. That is to say, plant-human practices enact worlds in which nonhuman beings, together with humans, participate (Apffel-Marglin 2011). Thus, I consider healing practices – specifically ayahuasca ceremonies, singing ikaros, and dieting plants (samá) – to be interspecies worldmaking practices. While not trying to delineate the bounds or existence of worlds to which I may not have access, I attend to the heterogeneous worldmaking practices performed by both plants and humans (Blaser 2014b). Specifically, I follow practices associated with the production of ayahuasca, from harvesting to trade (Chapter 3); practices associated with healing, like ceremony, singing, and dieting (Chapter 4); practices associated with research and Indigenous ways of knowing (Chapter 5); and community-based forest management (Chapter 6). I also approach my own writing as a worldmaking practice, which can either open or close ontological possibilities from the realm of analysis (Blaser and de la Cadena 2018).

Scholars studying the globalization of ayahuasca tend to focus on the new cultural forms and practices of shamanism that have been adopted as ayahuasca spreads within and outside of the Amazon from an anthropological perspective (Taussig 1987; Labate 2014; Labate and Cavnar 2011; Tupper 2009; Fotiou 2016; Brabec de Mori 2014; Talin and Sanabria 2017). This global phenomenon has not been investigated with attention to the socionatural transformations, interspecies relations, and reconfigurations of power that occur as ayahuasca and Amazonian healing practices are adopted and adapted by global consumers. While I draw from anthropological texts, I use a political ecology and interspecies approach to show the ways in which ayahuasca has woven itself into various cultural contexts, and how its socionatural relations have shifted.

Ayahuasca offers a poignant and timely case for understanding how powerful and culturally important nonhuman beings participate in shaping more-than-human social worlds and economies. The ayahuasca economy in some ways is a departure from the previous extractive economies in the Amazon (Chapter 2). In other ways, it operates within the same system of power in which plants are objectified as resources. As ayahuasca is enrolled in capitalist systems as a commodity for exchange, however, its pathways of circulation do not conform to usual routes of trade. I trace the pathways through which ayahuasca’s component plants circulate to reveal that plants themselves play important roles in shaping their own commodity networks (Chapter 3). I argue that the ecological, physiological, and social relations in which ayahuasca participates shape the particularities of the ayahuasca economy and its trajectory of commodification.

Ayahuasca as a commodity is relatively unique in the way that Indigenous healing practices have accompanied ayahuasca’s global circulation. Healing practices in turn shift as they are adapted and translated into the Western milieu (Chapter 4). I use the concept of recontextualization (Bauman and Briggs 1990) to understand the consequences of outsiders adopting and adapting Shipibo healing practices. Recontextualization allows us to see how practices shift as the frame of reference (context) changes, and certain elements are left behind while others take on new meanings. I show that as ayahuasca and its practices emerge into Western contexts, social relations between plants, healers, and outsiders are reconfigured. As a result, power, knowledge, and healing become ‘humanized’ as opposed to pertaining to the plant spirit – construed as passive byproducts of the material plants. This excludes plant spirits from certain types of social relations. I argue that this constricts the social agency of the plant spirits, and the co-constitution of relational worlds in which plant spirits are animated. At the same time, the spiritual power of the healers is routed through economic mechanisms. I argue that recontextualization of healing practices has resulted in a de-animation of plant spirits and an increase in the power attributed to humans. This has helped allow ayahuasca to become a commodity and object of analysis as opposed to a being with its own ability to teach, act, and heal.

Ayahuasca tourism does represent a shift from previous relations between Shipibo and outsiders, which were more founded on extractive and exploitative labor relations and religious oppression (see Chapter 1). However, these relations are still embedded in the ongoing coloniality that has dominated Ucayali since Spanish colonization (Quijano 2000). Histories of Indigenous enslavement and exploitation that powered extractive industries in the Amazon have constructed racialized hierarchies that still govern Indigenous lives and livelihoods (Chapter 2). As such, ongoing structural racism linked with the extraction of natural resources continues to limit Shipibo healers in benefitting from the commodification of ayahuasca and ayahuasca ceremonies. I show that within present-day commodity networks formed around ayahuasca, Indigenous healers are increasingly construed as replaceable and redundant, and are sometimes valued more for their labor and representation of indigeneity than they are for their ability to command spirits or their knowledge of plants (Chapter 4). Furthermore, demands of foreign consumers for translation and comfort have made it so that healing centers catering to tourists are expected to offer a more ‘luxury experience’ than many Shipibo healers are able to provide.

Westerners are increasingly determining the frame of operation for Shipibo healing practices (Freedman 2014). I look critically at discourses on healing and indigeneity and how certain narratives influence the relations among foreign participants, plants/plant spirits, and Shipibo healers. I show that individualized views of healing and the body, along with materialist and instrumentalized ways of understanding plants, limit plant-human relations and their ability to co-create worlds in which both participate (Chapter 4). This also reduces the social power of Shipibo healers whose expertise lies in navigating relations with plant spirits. Science and other academic ways of knowing have oppressed and restricted the way that both Indigenous knowledges and plant knowledges are valued and legitimated. I explore the breadth of research practices used to know ayahuasca and argue that Indigenous methods offer important ways of knowing and relating that are not available through science or social science methodologies (Chapter 5). I further examine how researchers, including myself, also contribute to the objectification of plants and Indigenous peoples. I explore how some of these hierarchies may be problematized by following Indigenous methods and community engagement, through a participatory forest management project I helped facilitate in a Shipibo community (Chapter 6).

Relating with ayahuasca through Indigenous practices offers important and powerful methods of disrupting hierarchy and understanding one’s own humanity. However, when healing only flows in one direction, when plants become capitalist commodities, and when Indigenous healers become wage laborers, we need to consider who is benefitting from ayahuasca’s global popularity. I draw distinctions around the tensions between capital, development, and ayahuasca, illuminating which elements of this process reinscribe global hegemonic power dynamics, as well as ways that some of these dynamics are disrupted. Though ayahuasca can offer powerfully transformative experiences for westerners who seek it, I argue that true healing must extend beyond the individual’s process and into the socionatural networks and systems in which we participate.

Click the image below to see Laura giving a short talk in 2018 covering part of her dissertation work.

Read some of Laura’s publications in the following links

Next Step

After graduating, I am excited to join Dr. Tracey Osborne’s research group at UC Merced as a postdoctoral researcher.

Laura’s dissertation research has been funded by the following agencies and awards

- Graduate Research Fellowship | NSF

- Berkeley Graduate Fellowship | UC Berkeley

- Sustainable Forestry Continuing Fellowship | ESPM

- Foreign Language Area Studies Fellowship, CLAS

- Bill Kuni and Mary Yang Summer Fellowship | College of Natural Resources

- James Duke Ethnobotanical Fellowship | ACEERS

- Research Support | Alianza Arkana

- Graduate Student Award | Association of Environmental Professionals

References

Apffel-Marglin, Frédérique. 2011. Subversive Spiritualities: How Rituals Enact the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bauman, Richard, and Charles L. Briggs. 1990. “Poetics and Performance as Critical Perspectives on Language and Social Life.” Annual Review of Anthropology 19: 59–88.

Blaser, Mario. 2014a. “Ontology and Indigeneity: On the Political Ontology of Heterogeneous Assemblages.” Cultural Geographies 21 (1): 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474012462534.

———. 2014b. “Ontology and Indigeneity: On the Political Ontology of Heterogeneous Assemblages.” Cultural Geographies 21 (1): 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474012462534.

Brabec de Mori, Bernd. 2014. “From the Native’s Point of View: How Shipibo-Konibo Experience and Interpret Ayahuasca Drinking with ‘Gringos.’” In Ayahuasca Shamanism in the Amazon and Beyond, edited by Beatriz Caiuby Labate and Clancy Cavnar, 206. Oxford Ritual Studies. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Cadena, Marisol de la. 2015. Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice across Andean Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press Books.

Fotiou, Evgenia. 2016. “The Globalization of Ayahuasca Shamanism and the Erasure of Indigenous Shamanism.” Anthropology of Consciousness 27 (2): 151–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/anoc.12056.

Freedman, Francoise Barbira. 2014. “Shamans’ Networks in Western Amazonia: The Iquitos-Nauta Road.” In Ayahuasca Shamanism in the Amazon and Beyond, edited by Beatriz Caiuby Labate and Clancy Cavnar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. How Forests Think. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Labate, Beatriz Caiuby, ed. 2014. Ayahuasca Shamanism in the Amazon and Beyond. Oxford Ritual Studies. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Labate, Beatriz Caiuby, and Clancy Cavnar. 2011. “The Expansion of the Field of Research on Ayahuasca: Some Reflections about the Ayahuasca Track at the 2010 MAPS ‘Psychedelic Science in the 21st Century’ Conference.” International Journal of Drug Policy 22 (2): 174–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2010.09.002.

Labate, Beatriz Caiuby, Clancy Cavnar, and Alex K. Gearin. 2017. The World Ayahuasca Diaspora: Reinventions and Controversies. London: Routledge.

Labate, Beatriz Caiuby, and Gustavo Pacheco. 2011. “The Historical Origins of Santo Daime: Academics, Adepts, and Ideology.” In The Internationalization of Ayahuasca, edited by Beatriz Caiuby Labate and Henrik Jungaberle. LIT Verlag Münster.

Pollan, Michael. 2018. How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence. New York: Penguin Books.

Quijano, Aníbal. 2000. “Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America.” International Sociology 15 (2): 215–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580900015002005.

Talin, Piera, and Emilia Sanabria. 2017. “Ayahuasca’s Entwined Efficacy: An Ethnographic Study of Ritual Healing from ‘Addiction.’” International Journal of Drug Policy 44 (June): 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.02.017.

Taussig, Michael. 1987. Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tupper, Kenneth W. 2009. “Ayahuasca Healing beyond the Amazon: The Globalization of a Traditional Indigenous Entheogenic Practice.” Global Networks 9 (1): 117–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00245.x.