Seventeen new species of plant bugs—a group of insects with a strawlike mouth used to feed on plant and animal matter—have been identified on the islands of French Polynesia, and their names honor scientists, actors, and Vice President Kamala Harris.

The insects were collected by Environmental Science, Policy, and Management alum Brad Balukjian, PhD ’13, who conducted field research on Mo’orea, Tahiti, and other nearby islands from 2007 to 2009, and again in 2011 as part of his PhD. The findings were published in late September in Insect Systematics and Diversity and challenged earlier taxonomic classifications that relied primarily on insect morphology.

“I knew that before I could answer any mechanistic scientific questions about the evolution of these bugs, I had to first understand what they were,” said Balukjian. “I became, without expecting it, a taxonomist and realized that the main focus of my research was going to be figuring out what these species are.”

Since completing his PhD, Balukjian has continued his research on plant bugs, published books on baseball and professional wrestling, and founded the Natural History and Sustainability program at Merritt College in Oakland. He is currently launching a new educational outreach project in French Polynesia called the Manumanu Project—operated in collaboration with the UC Berkeley Gump Station and the non-profit Te Pu Atitia—which will teach fifth-graders about insects to inspire the protection of biodiversity.

Rausser College spoke to Balukjian to learn more about his research, career, and plans for the Manumanu project.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What drew you to studying plant bugs in Mo’orea and Tahiti?

Islands and island ecosystems are kind of a throughline in what I've done, what I continue to do, and my passion. While I was an undergrad at Duke University, I created a self-designed major in island biogeography. I then worked at Islands magazine as an editor and was later drawn to the lab of Professor Rosemary Gillespie, who has written so many wonderful papers and articles about her work on island systems. She's also an arachnologist—I was never so keen on spiders, but I always liked insects.

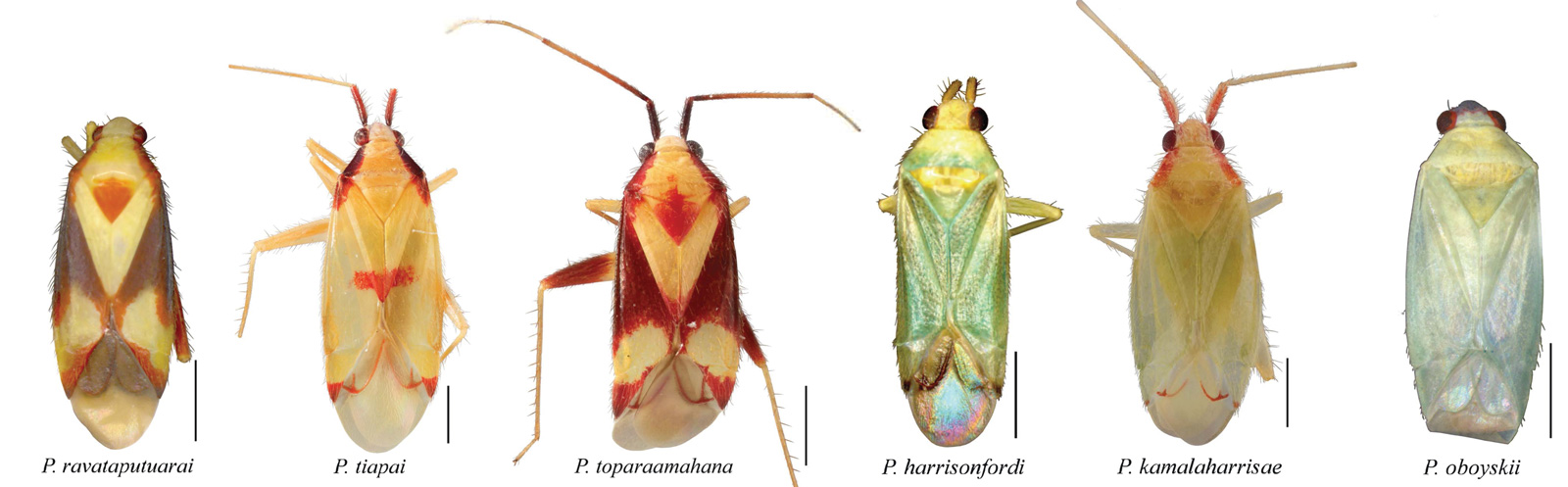

I was specifically drawn to a group of insects called plant bugs, which are a type of true bug (Hemiptera) in the family Miridae that are generally associated with plants. Within Miridae, there is a particular genus of insects known as Pseudoloxops—I called them the green flash bugs because they have this very distinct shiny, bright green appearance. Someone had done a survey on the remote Austral Islands of French Polynesia and found a bunch of these bugs, but no one knew what they were. I love that spirit of discovery, so I started to develop a project around these particular types of bugs on these remote islands.

What did you find?

There had only been one study of these bugs before, and it was done 100 years ago. The study presented a hypothesis that there are six species and identified where they were on what islands. The act of identifying species is a hypothesis-driven process done by taxonomists, who take a group of individual specimens and come up with a hypothesis of where the boundaries are between species. In the past, what taxonomists did was describe species based on their morphology. They would take big groups of specimens and group them into bins of similar-looking organisms, which they thought represented species that were reproductively isolated and different from each other.

I came in to test those century-old hypotheses with a lot more tools at my disposal. When DNA sequencing technology emerged, people could actually examine DNA to look at the genetics and the genes of specimens. That changed the game—it led to what I think of as a more complete and rigorous way to approach taxonomy, which is to take every possible line of evidence that could distinguish different species and examine that for as many specimens as you can. So my approach, in an integrated taxonomy framework, was to collect as many of these plant bugs as I could and then, for each individual specimen, measure and describe its morphology but also sequence its DNA and record what plant and island it’s found on. In doing that, I found an additional 17 species and confirmed three of the original six species. The other three species were what we call sunk—in other words, our research found these are actually the same species and that they're not different.

How did you settle on the names of these new species?

The first year I was in Mo’orea, I taught kids about biodiversity and insect biodiversity through the local elementary school. So when it came time to name the species, I thought it was really important to have them involved not only because these kids had helped me collect specimens, but because the insects are endemic to those islands. I gave the students pictures and information about each species and its characteristics, and then they came up with names in Tahitian to give to the species. Those names were checked by my collaborator, Hinano Murphy, who runs the nonprofit cultural association called Te Pu Atitia in Tahiti. She's also involved with the Gump Station in Mo’orea. She helped check all the names. I also named one in honor of Rava Taputuarai, a Tahitian botanist.

Pete Oboyski, now executive director of the Essig Museum of Entomology, collected the specimens of one species and worked with me on Mo’orea at the time. I wanted to honor him with the name of the species (Pseudoloxops oboyskii) that he had collected. And I’ve always liked Harrison Ford as an actor, but he’s also been an advocate for conservation and works on the board of Conservation International. So, I wanted to honor him for his work in that space with the name of one species (Pseudoloxops harrisonfordi).

I also named one species (Pseudoloxops kamalaharrisae) after Vice President Kamala Harris. This all happened before she was the Democratic nominee for president—I actually proposed this name years ago because it takes a while to get through the publication process. I appreciated that she was from Oakland because after I finished grad school, I built a whole community college program at Merritt College called Natural History and Sustainability, which focused on training students to get local environmental jobs. Around the same time, she and President Biden created the American Climate Corps, which is a nationwide initiative to train more environmental workers. It dovetails very nicely with the work that I did at Merritt, so I wanted to name a species in honor of her.

Can you tell us more about your work at Merritt?

When I was growing up, I was basically told that if I really loved animals, plants, and bugs, then I should get a PhD. I loved my experience in grad school, but I also realize that some people might not want to do four years of undergrad and then seven years of a PhD just to pursue their passion for nature. I wanted to give them a pathway that could get them going more quickly.

Merritt had great classes on natural history and environmental classes, but at that point, the program was really geared toward older people who just wanted to come in for their own learning or enrichment. There’s a pressing need for more environmental work, and fortunately, we're in the Bay Area where there's so much of that work that can be done. We decided to recast the Natural History and Sustainability program as a career education and certificate program that gives you internship experience and gets you connected with potential employers. Students have gone on to entry-level jobs in environmental consulting; within the East Bay Regional Park District and at state and national parks; or at nonprofits.

Do you hope to continue educational outreach in French Polynesia?

One of my greatest thrills is that, when I was in Mo’orea for a year and teaching fifth grade, one of my students went on to found and run this amazing nonprofit called Coral Gardeners. It’s one of the biggest nonprofit successes in Tahiti, and he was in my classroom. But when that year ended, the infrastructure and program that I had built continued for only another year or two because it was only temporarily funded. What I really want to do is help create a permanent scientific and educational infrastructure in Mo’orea classrooms, so that I can help train teachers to use this curriculum whether I'm there or not.

The Manumanu project will be independent of outside forces. I want to give teachers a manual about how they can use local biodiversity within educational standards to teach science topics and get kids excited about their own biodiversity. The idea is to offer a four-week program involving four different schools. We’ll go to a fifth-grade classroom in each school and teach them how to identify seven common orders of insects. We’ll give them the lessons in basic insect biodiversity and identification, then we’ll go out in the field and collect as many insects as we can. Because my specialty is these plant bugs, we would be able to identify those all the way down to the species level. But insects are so diverse that the rest of the insects we’ll identify down to the order. They’ll learn how to collect and identify insects using microscopes and come up with a total of how many species each classroom found. In the last week, we’ll have a science fair for the community, where students can present their specimens and findings to the public.

The idea is that by doing this at schools in different parts of the island, you can compare diversity and abundance between different locations. In future years, once the teachers have been trained on that curriculum, they can continue doing it while I would work with four schools on a different island and train the next set. If it goes as planned, you would get 25 years of data from the first four schools in Mo’orea, and then you'd have additional data from other islands to compare the insects on all these different islands over time.

READ MORE:

- 17 New Species of Plant Bugs Identified in French Polynesia, With Help of Local Students (Entomology Today)

- Kamala is bug: Bay Area biologist names new species for the veep (San Francisco Standard)

- I named a bug after Kamala Harris. Here’s Why (San Francisco Chronicle Op-Ed)