[image caption]

Choosing their path, making an impact

Rausser College’s Conservation and Resource Studies program celebrates 50 years of interdisciplinary, student-led scholarship

This is the first in a series of stories commemorating 50 years of the College of Natural Resources at UC Berkeley. Look for more stories in 2024.

It was the early 1970s—half a century ago. Antiwar protests were common. Unmarried couples got the right to use contraceptives. Richard Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. The Beatles broke up. In the San Francisco Bay Area, the BART system was taking its first passengers. The Free Speech Movement and hippie culture were in full swing.

The Clean Air and Clean Water Acts were beginning to address pollution around the country, the Environmental Protection Agency was founded, and there was an awakening consciousness about the importance of protecting the Earth. On the Berkeley campus, a group of faculty and students wanted to live ecologically and devote their careers to helping the environment. It was in this setting that the Conservation of Natural Resources (CNR) major was born.

A true collaboration between faculty and students, the new program took an interdisciplinary approach to environmental problems, with the goal of delivering the best solutions for nature and humanity. Flexibility was a core ethos: each student designed their individual focus area and selected courses, with faculty mentorship, from departments across the University. Many students earned credit for practical experiences including fieldwork, internships, and community involvement—activities that were seen as essential to making connections between theory and practice and choosing future careers. Those involved in the program also valued creating a community and a democracy, where students, faculty, and staff worked cooperatively and participated jointly in decisions.

“The [program] offers students the opportunity to receive an interdisciplinary education,” wrote U.S. Congressman Ronald Dellums (MSW ’62 Social Welfare), in a 1981 letter to then-UC Berkeley Chancellor Ira Michael Heyman. “In addition, its course of study is one which is vital to the future of our society.”

The program has evolved over the years, including a name change to Conservation and Resource Studies (CRS). And though Berkeley and the world may look very different from those early years, the core elements of the major still exist today—as do the benefits of cross-departmental study and the importance of taking tangible action for change. This year, Rausser College of Natural Resources celebrates 50 years of this groundbreaking major.

Interdisciplinary Environmentalism

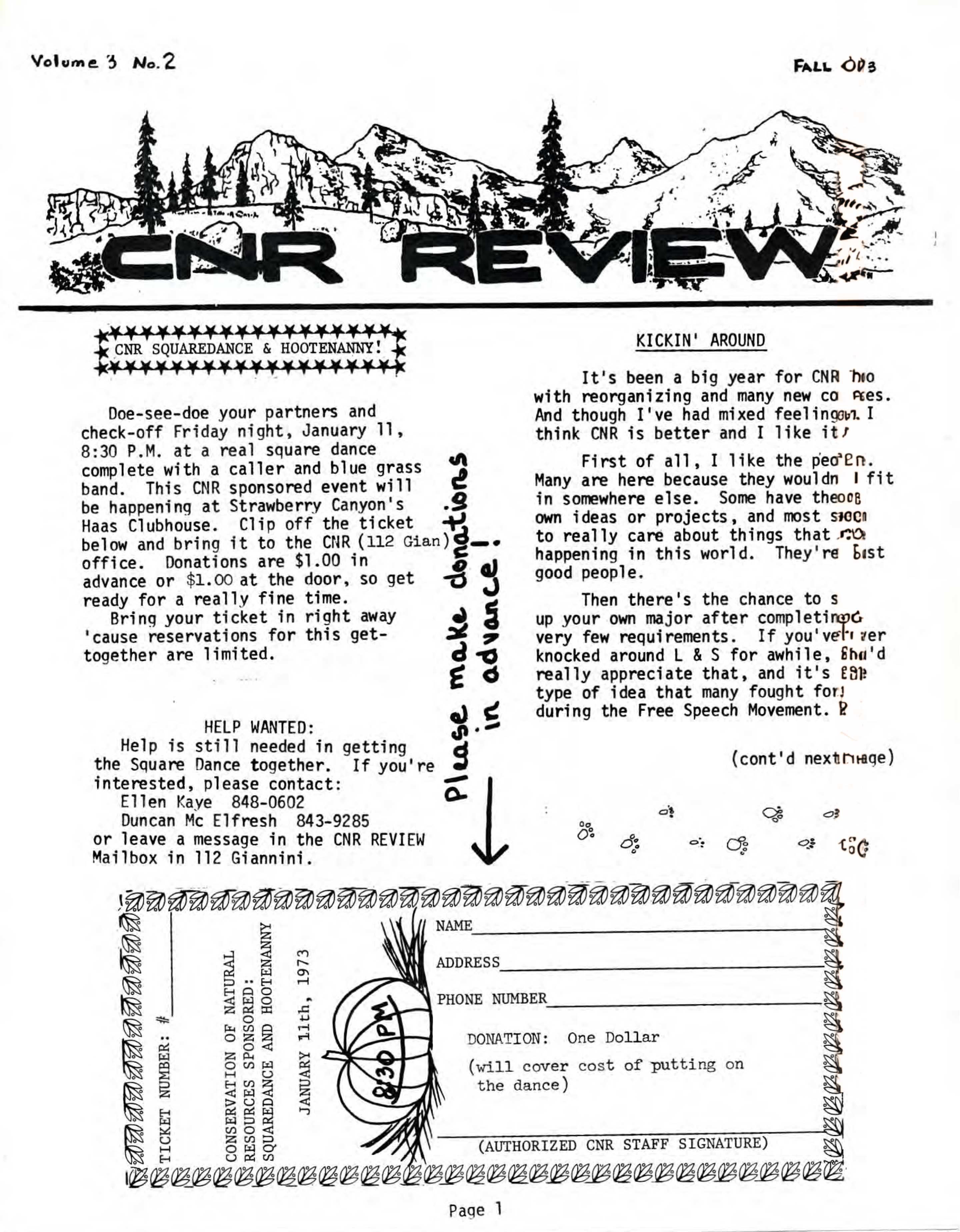

[image caption]

The beginnings of the program date back to 1969 with plans made by the College of Agricultural Sciences and the School of Forestry and Conservation to create an environmental studies major for undergraduates. In a history of the major compiled in the 1980s, then-professor Paul L. Gersper and Alan S. Miller, an academic coordinator and lecturer, wrote that the “accelerating environmental movement” was a major impetus for the new program, which offered its first course in the fall of 1969. The three-quarter interdisciplinary course sequence titled "Man and His Environment—Crises and Conflicts" was required for CNR majors. “By the winter quarter of 1970, 100 students were enrolled in the new Conservation of Natural Resources Experimental Field Major,” the report states.

“The CNR program can best be described as an experimental, interdisciplinary, environmental educational program whose primary focus is the identification, understanding and resolution of complex and highly interrelated environmental issues taken in their societal context. The activities of the program are directed towards the design of effective, holistic and systemic methods appropriate to this comprehensive focus,” wrote Loren Cole, PhD ’75 Ecosystemology, in his 1975 dissertation that chronicled the development of the program.

According to another report on the major authored by then-professor of education and program co-founder John Hurst in 1981, “CNR provides a holistic interdisciplinary education focused on the understanding and solution of environmental problems. It strives to achieve meaningful freedom and a broad range of choice for its students within a humane and supportive milieu.” The program’s flexibility for student-driven course selection, emphasis on experiential learning, and strong community, attracted students who were passionate and self-directed.

“It was a really creative place,” said Anne Parker, BS ’74 CNR, one of the first graduates of the program. “The faculty actually listened to us; we were co-creating and actually designing things together. Berkeley's big, but being in the program was like having a family.”

After introductory courses and other breadth requirements, students worked with faculty advisors to develop their Area of Interest and a plan for upper-division courses across departments. These basic elements of the program still exist today. “There was no other program like it at the time,” said Gordon Frankie, BS ’63 Entomology, PhD ’68 Entomology, an emeritus professor who taught a core course in the program for 20 years and served as the major advisor for 13. “It was and still is quite unique.”

Ellen Kaye Gehrke, BS ’75 CNR, valued the opportunity to develop courses with faculty on leading issues of the time. “We felt freedom and equality, with faculty that respected us and allowed us to participate jointly in decision making,” she remembers. “Some environmental issue would be in the news, and we’d have a class on it next quarter. It felt really cutting edge.”

According to Cole, who served as the CNR program’s coordinator in the early years and was heavily involved in program planning, course design, and coordinating advisors, “participants always knew that they would never be turned away and that their ideas would not be judged as naive or stupid. They began to adopt innovative and insightful ideas in their search for knowledge and understanding. They were not afraid to explore new perceptions and question the underlying assumptions of their interests and values. They began to learn.”

During the first years, there was very little institutional funding for faculty, facilities, or staff. According to Gersper and Miller’s report, “more than thirty faculty volunteers taught or helped teach the new courses in the program, served on committees, and offered their time as academic advisors,” and hundreds of additional faculty and off-campus volunteers lectured, participated in seminars and field trips, served as information resources for students, and sat on committees.

“...most of the credit should go to a group of faculty who relinquished their fears to the potential that this new approach might offer,” wrote Cole. “They demonstrated that rare gift of being able to break out of their own paradigm and redirect their efforts towards a new and untested one. There are no words to express the difficulty of this action or the immense implications of their contributions.”

The importance of faculty engagement

One faculty member who was instrumental in the founding of the major was Arnold Schultz, a professor of forestry and resource management. Schultz coined the term “Ecosystemology” for a course he introduced as part of the major. As defined in Schultz’s 2009 course reader, ecosystemology is the science of ecosystems, which Schultz understood to always include human beings and their ideas, values, and cultures. There was a heavy emphasis on “systems thinking,” which means thinking in terms of relationships, patterns, and context. “We were taking disparate bits of knowledge from various fields and classes, and putting it back into a system, to decide what we’re going to do to help the Earth,” said Parker. In remembering their CNR education, many of the early students noted how influential systems thinking has remained in their lives.

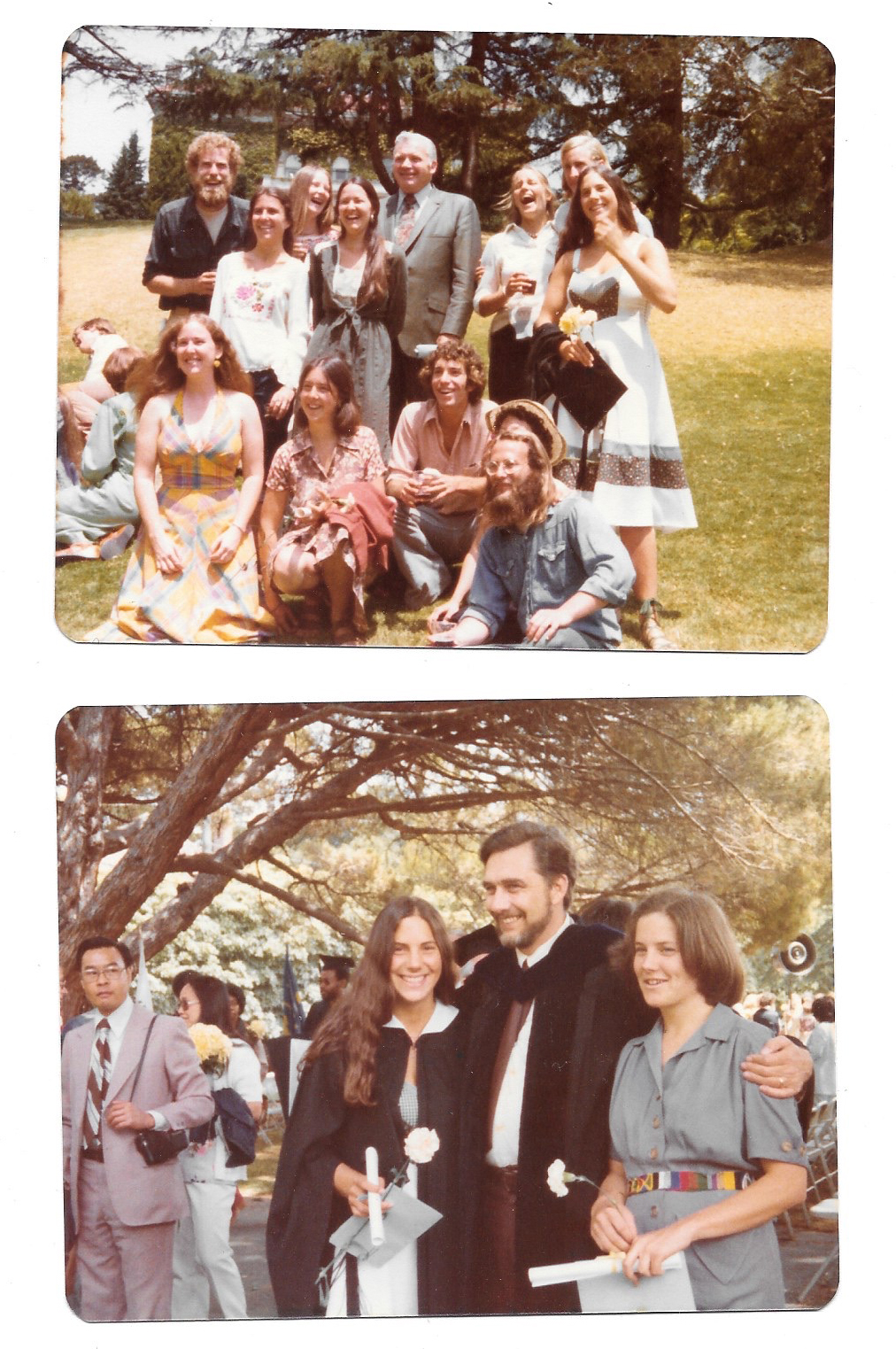

[image caption]

Schultz also taught “Environmental Problems: Principles and Methods of Analysis,” another core course in the major. According to a faculty remembrance of Schultz written by professors Joe McBride and James Bartolome, his lectures “filled the auditorium in Mulford Hall with eager students, and incorporated poetry, dramatic art, parables, cooking, and hard science in an ever-evolving format aimed at stimulating thinking on the part of his students.”

Schultz’s 2009 course reader used images to fill in blank spots, but these were more than mere illustrations. He wrote “Remember the credo: EVERYTHING IS CONNECTED! So even the fillers will have a connection to everything else in the Reader.” The caption next to a tessellation of birds read “This is not a filler. It’s very important stuff. See the connections? Read about tessellations in Chapter 9.”

“I’ll never forget the lecture when Arnold Schulz and Frank Pitelka [then a professor of zoology and a well-known academic in the field of behavioral ecology] spoke about the work on the lemmings and the tundra, and the operation of nutrient cycling and predator prey relationships and how it all fit together," said Larry Ruth, BS ’77 Political Science, PhD ’90 Jurisprudence and Social Policy, who took many CNR courses and later worked as a researcher and instructor in the College of Natural Resources. “There must have been nearly 500 people there. It was electric.”

Schultz, who was beloved by the students, also led an annual field trip to the pygmy forest in Mendocino County. “He made connections with people that normally never would come together from different departments and different schools,” remembered Lauran Hawker, BS ’77 CNR. “He just had a way with people.” According to other early CNR students, Schultz would invite students on research trips in various places ranging from Mount Kilimanjaro to Israel.

Experiential learning and field trips have remained important throughout the years. During his years teaching ESPM 100, Frankie took students on field trips all around the state. “We’d go to wine country and learn all about agriculture and integrated pest management, or we’d go to the Central Valley and learn about marshes supporting migratory waterfowl, or we’d travel to Sly Park Recreation Area,” he said. “Environmental education was so important for these students; they wanted to not only get an education but also go do something with it.”

Ignacio Chapela, the current faculty leader of the CRS group, often takes students kayaking or on “moon worm walks,” as community-building exercises. Many current students comment on those outings, as well as the importance of office hours with Chapela. “There are always a handful of students there talking, and we might talk about courses but other times the topics get really broad, insightful, and eye-opening,” said Thuy-Tien Bui, BS ’23 CRS. “As individuals we may have different interests but we are all analytical and passionate, and being in one space together during office hours is really impactful,” said Isabel Cabrera, a junior CRS major and co-president of the Conservation and Resource Studies Student Organization.

Living and learning

Fostering community was extremely important for the students who founded the program fifty years ago as well. Back then, much of the connection happened off campus at a house on Ellsworth Street, which came to be known as The Green House. Tom Javits, BS ’74 CNR, one of the first residents, said it all began during a course called “Environmental Lifestyles,” which met on the lawn of Giannini Hall every Wednesday. “We envisioned a house that could promote and demonstrate environmental or ecological lifestyles,” said Javits. “The term ‘sustainability’ wasn’t even being used yet at that point.”

Eight students lived in the old Victorian, paying $485 per month in rent, hosting classes in the attic, and raising vegetables, chickens, and rabbits in the yard. Kaye Gehrke remembers that the group would volunteer at the recycling center started by Bill Olkowski, PhD ’72 Entomology, most Saturday mornings, then they’d pick up the produce they had ordered through The Berkeley Food Conspiracy—a network of groups that pooled their money to buy and share large quantities of fresh vegetables, dry goods, and cheese from Oakland produce wholesalers. “The house was really an incubator of ideas about environmentalist lifestyles and understanding what it could mean to live sustainably in a city,” Javits said, noting that some 30-40 students occupied the house over the course of 5-6 years.

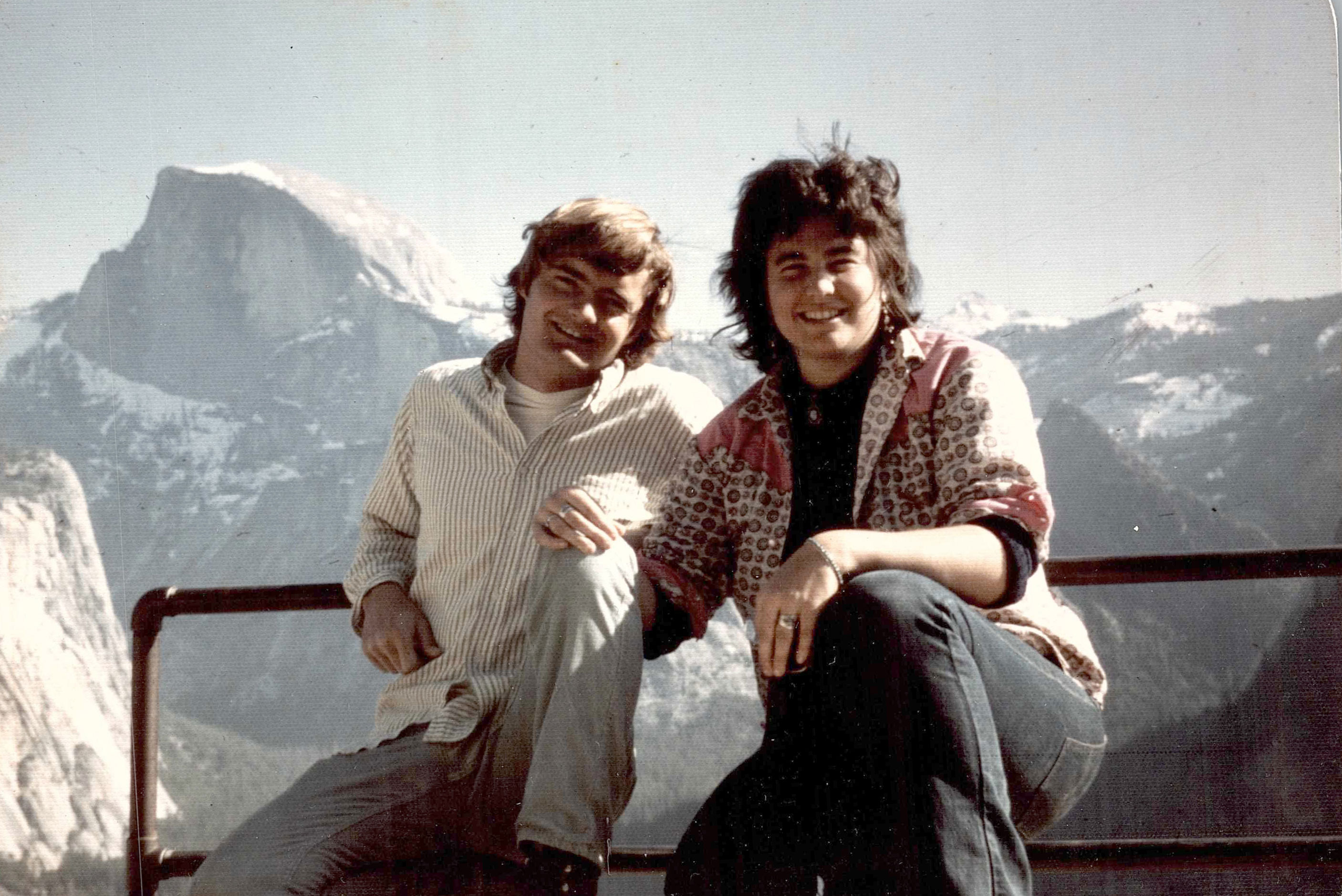

California State Senator Nancy Skinner, BS ’77 CNR; MA ’89 Education—one of the major’s many notable alumni—fondly remembers stumbling upon the Green House, which then led her to the CNR program itself. “CNR set me on the life path, and thank goodness—it saved me from the Russian Literature major I was pursuing at the time,” she wrote in remarks shared at a CRS 50th Anniversary Celebration held at the Blue Oak Ranch Reserve in Santa Clara County in Spring 2023. “When I learned that CNR majors were doing self-sufficiency projects, getting credit for internships, and taking field trips to Yosemite, I knew it was the major for me.”

[image caption]

Skinner noted the influence professors like Schultz, Gersper, Donald Dahlsten, Joseph Hancock and other lecturers in the program had on students: “They would urge us to take learning to work and get involved in community efforts like recycling, lobbying the city to ban pesticides, and working on campaigns like the one to municipalize PG&E,” she wrote. “What's a good student to do? Of course I got involved in these community efforts. Next thing I knew I was walking precincts and registering students to vote.”

Experiential explorations

Learning through action was at the heart of the CNR program, and many early alumni were involved in internships or volunteer work that informed their education and careers.

A number of CNR students became involved in the Integral Urban House, another example of urban homesteading founded by UC Berkeley architecture professor Sim Van der Ryn and Olkowski and his wife Helga. The intention was that the house would demonstrate to the public what self-sufficiency looked like by combining, or “integrating,” principles of energy and water conservation, urban agriculture, domestic waste recycling, solar energy collection, home composting, and in-house food growth.

Many students also had the opportunity to work as home energy auditors with Arthur Rosenfeld, a Berkeley physics professor and renowned advocate of energy efficiency. “With the help of CNR students, Rosenfield had a major impact on the California energy system, which became a model for other states,” said Richard Norgaard, BS ’65 Economics, a faculty member who taught in the CNR program.

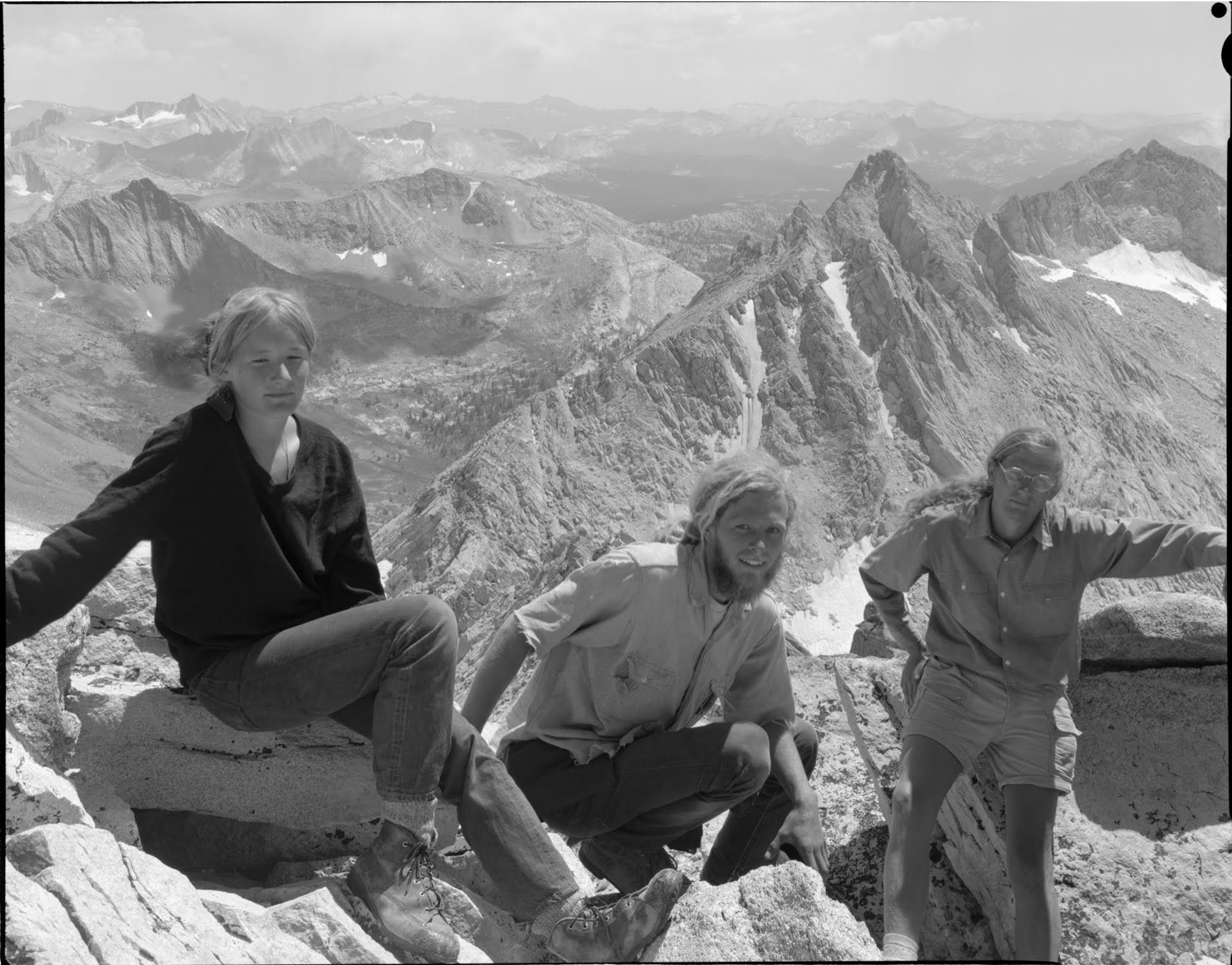

Another off-campus experience that was pivotal for many students in the early years was a multi-year effort to create one of the first wilderness permit programs for Yosemite National Park. There was a dramatic increase in the number of people interested in hiking and backpacking the backcountry of the park but very few rangers devoted to those areas, leaving many to grow concerned about human impacts on the ecosystems and wildlife. Led by Dan Holmes (BS ’73 CNR, MA ’76 Geography, MLS ’83 Library & Info Studies), a group of CNR students conducted impact studies and gathered information about trails across the park.

[image caption]

“We walked on every single trail in the park, hiked nearly every single feasible cross-country route in the park, and circled almost every single lake in the park,” said Margo Matthews, BS ’71 Forestry.

They corrected United States Geological Survey map errors—something now done with remote sensing—and provided information for trail guides in exchange for a few dollars a day. The group documented fire rings and other human impacts across the park and produced a report for the National Park Service as well as a map—drawn by Joseph Holmes, BS ’73 CNR—showing fire ring locations and sizes. The next step was implementing a voluntary backcountry permitting system and encouraging hikers to utilize it, then monitoring use.

“The Yosemite experience was life changing for me,” said Matthews. It led to her first job as a backcountry ranger in North Cascades National Park, followed by a few years at Mount McKinley National Park and then a long career working for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. “My CNR experience is what brought me into all this, and the Yosemite Project launched my career.”

Resistance and Evolution

[image caption]

Although the CNR/CRS program is popular among those who are a part of it, the program was not always well received. In 1974, the College of Agricultural Sciences and the School of Forestry and Conservation merged to form the College of Natural Resources. That same year, CNR was approved as a regular major and placed in the newly created Conservation and Resource Studies department. By 1976, there were more than 450 students enrolled in the program, which was now receiving support and facilities, including a Resource Center and Library, according to Gersper and Miller’s report.

Students were allowed to weigh in on the hiring of new faculty and pushed to recruit social scientists to complement the existing biological and physical scientists. In the mid-70s, Carolyn Merchant, Sally Fairfax, and Claudia Carr joined as the first female tenure track faculty in the program.

Over the first decade of the program, there were periods of criticism by many in the College and the University. Concerns were raised about the interdisciplinarity of the program, the level of student autonomy in crafting their own course of study or independent study projects, the close advising relationships between students and faculty, and more. “Berkeley wasn’t exactly a friendly ecosystem to this kind of endeavor,” said Rolf Diamant, valedictorian of the first class that graduated with a CNR major in 1973. “Faculty members who were involved were sometimes sailing against the wind. In some sense, they were ahead of their time.”

“There was one thing that held us all together as faculty, and that was the underlying awareness that what we did as teaching faculty was going to make an environmental difference in the lives and outlooks of the CRS students,” said Frankie. “They would carry forth with the knowledge that we were sharing. That was a driving awareness I felt every time I taught or even met with a single student.”

Several program reviews were conducted, expressing both criticism and support of the curriculum. The department applied for a graduate program similar to the undergraduate program, but was turned down during the 1978-9 school year. But support for the program and student interest persisted. A College Executive Committee that conducted a review in the Spring of 1982 saved the major from potential dissolution. The committee recommended changes including the establishment of a regular CRS faculty with full-time appointments, revised admissions procedures, changes for grading in "nontraditional" courses to pass/not pass, revised internship and independent study procedures, and standardization of the advising system, according to the report by Gersper and Miller. The changes proposed by the committee were enacted by the 1982-83 academic year and, according to Gersper and Miller, “these are then good dates to reflect the end of CNR and the beginning of CRS.”

Continuing traditions and creating change

The CRS approach may not be right for all students, but it has remained popular over the years. Merchant, who served as chair of the program from 1984-89, wrote in the 1986 program bulletin: “We hope to facilitate the interdisciplinary links between humans and nature, between past and future, between science and ethics that inspired the department’s creation in the early 1970’s. I encourage students who enjoy putting programs and ideas together in new and creative ways and who share a concern for the quality of human life and that of the natural environment to consider CRS as a major. As faculty and students, we reach out to each other, the community, and the globe to seek ways of resolving environmental problems. The excitement and inspiration of devising and implementing new policies, scientific approaches, and ways of thinking vitalize us. The hope that we may have some small effect on the Earth of the future unifies our study and work.”

Another interdisciplinary program with roots dating back half a century is the Energy and Resources Group (ERG), a collaborative community of students and faculty working across disciplines and departments, using tools from ecology, economics, engineering, and the social sciences. Norgaard, who taught in ERG in addition to the CNR program, notes that the two programs were similar in many ways. “Both groups were inspired by the work of Rachel Carlson, and were coming out of the free speech and environmental movements,” said Norgaard. “Faculty involved in these programs wanted to use participatory approaches rather than top-down education just telling students what to think.” According to Norgaard, experts on environmental and energy topics who were invited to speak to the ERG community often also spoke during the core CRS course as well. One of these notable speakers was Paul Ehrlich, author of the controversial 1968 book The Population Bomb, which warned of the population growth causing famine and resource depletion.

When Frankie arrived on campus as a professor in 1976, he found in the CRS program the type of learning and academic endeavors that had always been his passion. “Students need to know that not only are they getting an education, but they are also expected to go out and do something with it,” he said. “Once I got into [the program] I thought ‘This is it. This is where we ought to be.’”

For his course, Frankie also brought in guest speakers from all around the state to offer their expertise. “The course is about the huge diversity of environmental problems and how to solve them, and not one professor can do it, not two. Not three, not even four,” he said. He’d ask students for a 15-20 page paper, and sometimes they’d turn in 35: “That’s just how much they got into their chosen topic.”

While the department, major, and course names have evolved over the years, the core elements of the program are very much alive today. The major is now a part of the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, and a minor is offered as well. Every CRS student takes a course during which they create a major roadmap determining which courses will support their specific Area of Interest. “Students are the pilots of their education,” said Sarah Rhoades, the academic advisor for the major. “And Ignacio [Chapela], I, and the faculty advisors are like air traffic control, making sure things are going in the right direction.”

[image caption]

New technologies in energy, computing, data science, and other fields have opened doors for new areas of focus for students over the years. Rhoades said she’s seen students incorporate studies in everything from soil science and ecology to environmental policy, environmental justice, and clean energy, weaving in eco poetry or environmental education and all kinds of other topics. “The students are very solutions-focused,” she said. “They like learning about the theory, but then they also really want to get into what can be done about it.”

CRS students also value sharing what they’ve learned with others, which has many times resulted in student-led DeCal courses. Sage Lenier, BS '20 CRS, launched the popular "Solutions for a Sustainable & Just Future" DeCal in 2018, which offered a comprehensive environmental education and educated students on how to incorporate environmental solutions into their lifestyles. The course grew to over 300 students and was “passed down” after Lenier graduated to younger CRS students who continue offering it every year. Last spring, Bui and other seniors Caitlin Grace, BS ’23 CRS, and Addison Eftekhari, BS ’23 CRS, designed another DeCal called Bioregions of the Bay area, through which they led students on field trips about the region to learn about ecology, hydrology, energy, community connections, and Indigenous history to help participants connect more deeply with the space they inhabit.

Student involvement in recruiting new CRS majors and creating a welcoming environment for students in the group also remains core to the program. The CRS Student Organization (CRSSO) organizes socials, coordinates an “Adopt-a-Senior” program to connect older and younger students, and plans the major’s alternative graduation, known as “Alt-Grad.” Held on the same weekend as University and College graduations, Alt Grad is a more intimate event at a regional park in the area. Younger students present graduates with plants—"living diplomas," a tradition that goes back nearly to the beginning of the program, when deforestation was an issue in California and students wanted to avoid the use of paper. Students read poems, play music, or dance—every year is a little different—and after the ceremony, there is a celebration with food and drinks.

“It’s really meaningful to get away from the hustle and bustle of campus during graduation season, and knowing that the event was planned by students in the program really makes it intimate in a way that is so emotional,” said Bui.

Recently, the students started a new tradition during Alt-Grad, instituting awards that are not based on GPA, as major citation awards are. In response, the group created awards that honor a student who made an outstanding contribution within the CRS community, and a student who made an impact outside of the community.

Global and Local Alumni Impact

At the CRS anniversary celebration held last spring, Chapela reflected back on the origins of the programs in the 70s. “It was a time of an awakening consciousness of environmentalism,” he said, going on to reference the banning of DDT and other pesticides. “We’ve had great successes…ospreys and bald eagles returned, porpoises and sharks coming back to the Bay…but the problems just kept becoming more and more compounded. Deforestation became a concern, then biodiversity loss, energy problems, and nutrition and food systems came into play.”

[image caption]

Chapela added that the students he sees today have “eco-anxiety,” having been born into a world where Earth was already in serious crisis. “One student recently told me ‘we have it in our bones,’” he said.

But the overwhelming mood at the event was still positivity and hope. “The CRS program is visionary in its approach to environmental problem-solving,” said Hillary Lehr, BS ‘07 CRS, while moderating an alumni panel during the anniversary celebration. “It emphasizes systems thinking and collaboration across disciplinary boundaries, which maps nicely onto the very complex real world of policy and decision-making where there are folks who may not share our values or see the world as we do.”

“In the early 70s there was still the idea that you could have the hero scientist or the hero scholar who would come up with a new way of solving all environmental problems at once,” Chapela added. “But what we recognize today is that there is no solution to environmental problems without intergenerational responsibility and connectivity, because all these wicked problems of environmental science and practice are problems that would not be solved in one generation. So the building up of intergenerational responsibility networks has become a really central focus of practice within CRS.”

In her comments prepared for the anniversary celebration, Skinner said that the program was the training ground for students’ lifelong dedication to thinking globally and acting locally. “...it wasn't enough to just learn about environmental problems. We learned to use our knowledge and skills to try to solve those problems. That is what I and many of you have been doing ever since.”

The more than 4,000 graduates of the CNR/CRS program have taken varied and disparate paths, following their passions and creating positive change across fields and organizations, both locally and globally. They have served in local and state government positions, led environmental organizations, worked as conservation biologists and resource managers, advanced green building and construction practices, started nonprofits, engaged in environmental education, and much more.

“We sense something relatively unique in CNR students and graduates: they express a hope for the future,” wrote Hurst in a 1981 report about the impact of the CNR program. “Not a naive hope, but a hope fashioned out of a prolonged struggle with the crises confronting humankind, and the experience of relationship, support, and strength from working together to resolve these crises in a cooperative community.”

As the environmental crises evolved and intensified over the years, that spirit of hope and collaboration has continued to ring true for some of UC Berkeley’s brightest students. “Rausser College of Natural Resources is honored to celebrate the history and impact of this groundbreaking program and the important role it has played in our College over the past half-century,” said Dean David Ackerly. “We look forward to fostering many more years of student-directed education for the betterment of the planet."

See more photos of the CRS 50th anniversary event and listen to a recording of the panel discussions (transcript here).

READ MORE

- CRS program information for current students

-

Strawberries, succulents and saplings make unique 'living diplomas,' Berkeley News 2019

-

Ecosystemology course reader, Arnold Schultz, 2009

-

Looking Holistically: The Conservation Resource Studies Major, John Hurst, 1982

-

Implementation Aspects of an Ecosystems Approach: The Conservation of Natural Resources Program, University of California, Berkeley; 1969-1972, by Stuart Loren Cole, 1975

-

Conservation and Resource Studies Major: University of California, Berkeley, by Paul L. Gersper and Alan S. Miller