Margiana Petersen-Rockney, a fifth-year PhD student in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, was homeschooled on her mom’s diversified dairy goat farm in Massachusetts until she started college.

Not many academics studying farming systems come from a rural or farming background, and that is where Petersen-Rockney—who studies how rural agricultural communities in the United States are responding and adapting to climate change—stands apart.

“I’ve always felt tension between doing tangible work, like farming or working directly with farmers on the challenges they face, and having the capacity to effect structural inequities in our agri-food system through academic and policy work,” said Petersen-Rockney. “Often, we don’t see tangible change.”

But academia can help identify the structural issues causing problems for farmers and ranchers on the ground.

Between her undergraduate and graduate studies, Petersen-Rockney worked in the nonprofit world with farmers, many of whom were immigrant, refugee or beginning farmers.

“We would talk with farmers about pest management and soil testing, but soon came to realize that farmers often have that knowledge already,” said Petersen-Rockney. "A key problem is, many farmers don’t own the land they’re working and can be evicted at any moment.”

More than half of U.S. farmland is now rented for a few reasons. There are few regulations over who can buy, sell, and own farmland, and—mirroring broader societal trends—there is great inequality among those who farm.

Today, financial institutions count themselves among "those who farm." Corporations seeking to make short-term profits will buy up farmland and “develop” it—perhaps plant a few orchards, dig a few deep wells—in the hopes of reselling as fast as possible to the highest bidder.

It is not hard to imagine what results from this. When farmers are at risk for eviction, they are less likely to invest in more sustainable “diversifying farming” management practices such as crop rotations and integrating livestock and crops—vital acts which improve soil health and aid in carbon sequestration. Also, many tenant farmers and farm workers already contend with discrimination and exploitation based on race, ethnicity, language, gender, and class.

Over the last two years, Petersen-Rockney and a team of 17 other researchers from a diverse range of disciplines have been collaborating within the Berkeley Food Institute’s Center for Diversified Farming Systems to craft a newly-published, peer-reviewed paper titled "Narrow and Brittle or Broad and Nimble: Comparing Adaptive Capacity in Simplifying and Diversifying Farming Systems."

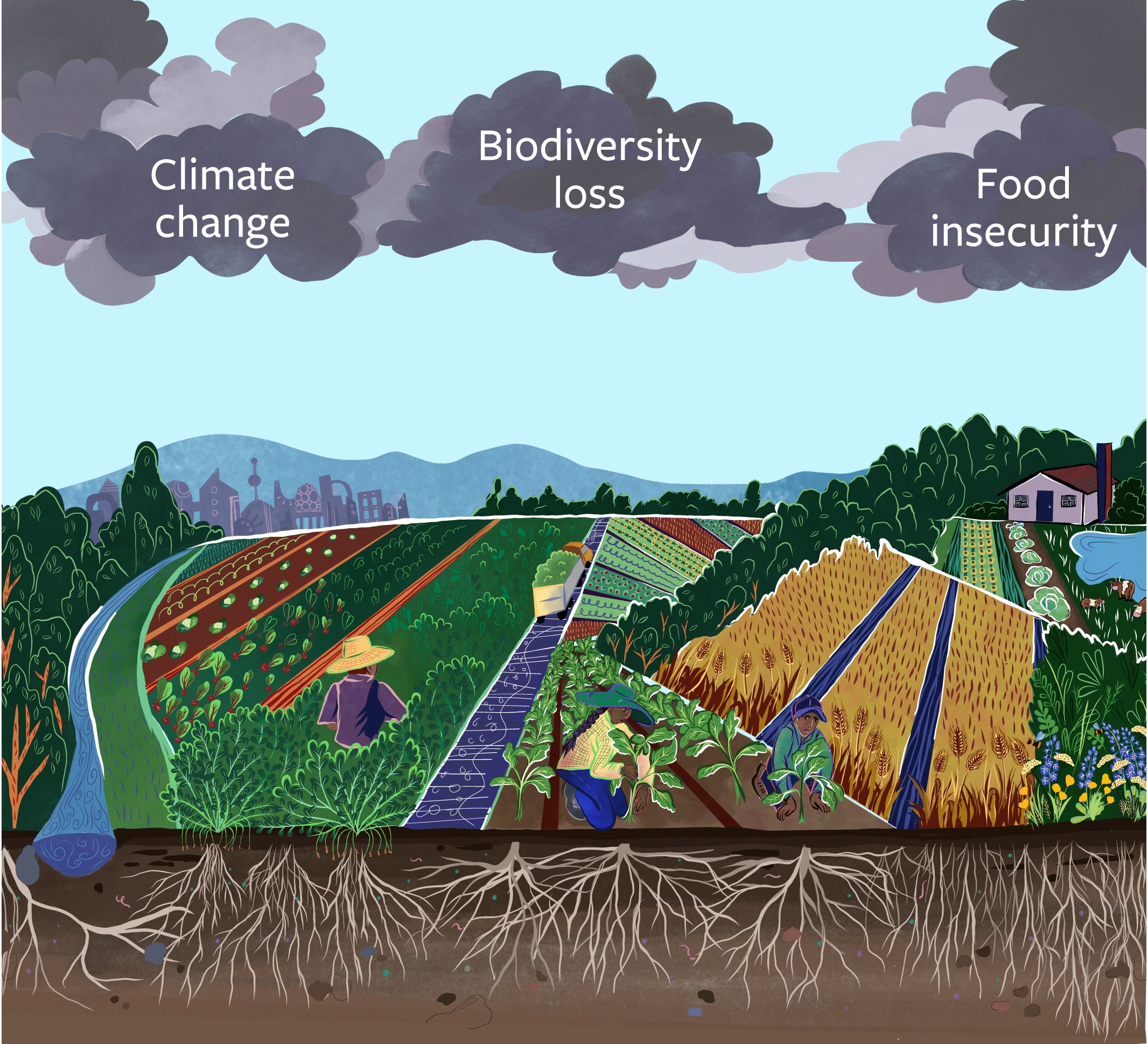

Essentially, Petersen-Rockney and colleagues examine how farming systems adapt (or don’t) to global threats like climate change, biodiversity loss, and food insecurity.

They compare farms’ capacity to adapt to such negative, shocking events through either 1) doubling down on the status quo of the "simplifying farming process,” or 2) adopting “diversifying” strategies. Across five case studies—including farm labor, drought, and land access—they found diversifying processes facilitate both social equity and greater environmental sustainability.

Currently, U.S. farmers mostly use “simplifying processes”—farming characterized by crop homogenization (ie: a farm only growing corn), a centralized market, and in general, incentives that prioritize profit over farm worker livelihood and well-being and natural resource conservation.

How did we come to practice this simplifying farming process? In the past, simplifying practices promised greater control and predictability, in the face of presumed steady conditions in the future. But the world is changing rapidly and these streamlined farming systems are proving to be vulnerable.

Today, for example, just four corporations control over seventy-five percent of the world’s global grain trade, and four seed companies now control over 60 percent of the global seed market.

“It’s essentially an oligarchy,” said Petersen-Rockney. “We need to implement antitrust laws. Farmers don’t ‘choose’ simplifying practices per se, but many are on a production treadmill, and to stay afloat they need to respond to consolidated markets— to both obtain farming materials like seeds and sell their farm products like grains.”

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Petersen-Rockney and her fellow authors witnessed firsthand how farms that have adopted this simplified farming strategy have been unable to adapt adequately to shocks and stressors such as floods—or a global pandemic.

“With the COVID-19 pandemic, more people are facing food insecurity, and frontline workers in food processing and packing have been disproportionately hit,” said Petersen-Rockney. “And in the meantime, farmers were forced to euthanize their animals, dump milk, and leave produce to rot.”

To move this matter even closer to home, research institutions like UC Berkeley are implicated in this simplifying farming process.

“Very little agriculture-related research and development money goes to study agroecology and other diversifying processes,” said Petersen-Rockney. “And more generally, research done at public universities with public funding should benefit the public. This means the products of that research shouldn’t be privatized in ways that mean only a few companies can access them and benefit.”

For example, if UC Berkeley scientists help develop a new variety of strawberries, that plant should ideally be publicly available so that smaller-scale farmers can afford it too, not just big corporations like Driscol.

Moving forward, Petersen-Rockney wants to continue to do “academic work that values and includes rural knowledge holders” and honors her background and privilege of growing up on a farm.

Because, in both her research and life, Petersen-Rockney has found one assertion reproduced again and again: “It’s often not an issue of knowledge (of farming, of farming systems) or lack thereof, it’s an issue of how power is currently allocated and who can do what.”

This article was lightly adapted from an article originally published on the Berkeley Graduate Division website.