By Stella Cousins, ESPM Graduate Student

I collect tree cores for both my research on the effects of drought and air pollution and for use as a hands-on teaching tool. Tree rings can tell great stories about changes in the world around us.

Though California’s agricultural and wildland resources are as extensive as they are diverse, 95% of our state’s population lives in cities. While some venture out for hikes and camping trips on the weekends, others have few options to experience the feeling of pine needles softening the trail under their feet, or the sudden rush of cool of the air as they round a corner and happen upon a stream. How can we, as environmental scientists, share our interest in and knowledge of the natural world with those who lack access to fields and forests? How can we ask them to care about something they hardly know?

It can be a challenge to make environmental patterns and processes relevant to people who are immersed in an urban experience. As a Graduate Student Cooperative Extension Researcher, I’m collaborating with three regional Natural Resources advisors to explore ways to overcome this challenge. Our work ranges from teaching natural history to youth to communicating the consequences of drought to forest managers. Through these efforts, we hope to introduce Californians young and old to the inner workings of the ecosystems we rely upon.

During the 2014 Shasta Forestry Institute for Teachers, US Forest Service personnel showcase a fuel reduction treatment in progress on the Lassen National Forest.

My academic interests involve understanding how and why forests change; specifically, my dissertation research examines the causes and consequences of forest mortality. A large part of my Cooperative Extension outreach work focuses on bringing forest ecosystems to life through involvement with the Forestry Institute for Teachers (FIT). The goal of FIT is to provide K-12 teachers with knowledge, skills and tools to effectively teach their students about forest ecology and forest resource management practices. The program brings together natural resource specialists and teachers from rural and urban settings for one full week in the summer, to promote a deeper understanding of forest ecosystems and human use of natural resources. The FIT program recognizes that “Environmental education, integrated into student's entire education, can help them learn how to make choices and decisions about issues like forest health, ecosystem management, consumption and local economies.” The free, residential program offers locally adapted content in four forest locations around California, and has served over 2,200 teachers since 1993. FIT participants follow through with their training by developing classroom curricula that integrate conceptual learning about forest ecosystem ecology and forest management practices.

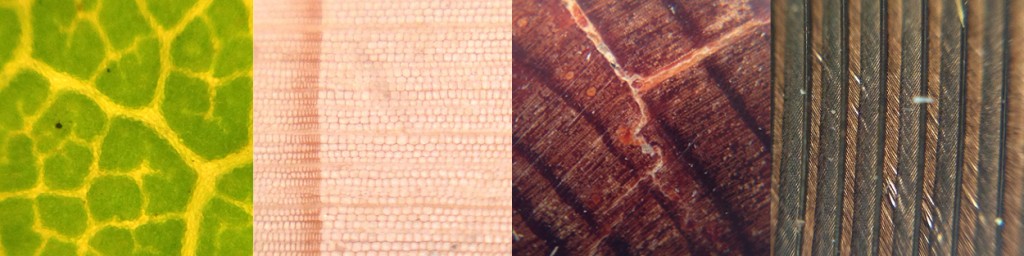

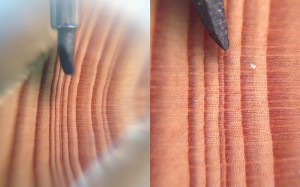

Images taken with miniature platform microscope and a smartphone, left to right: Venation and cells on the underside of a white oak leaf; A ponderosa pine core shows compact cells in late season wood followed by a new season of large-celled early wood growth; A burned ponderosa pine shows a scar and resin ducts resulting from a fire in 1773; A feather’s intricate structure is also visible with this simple setup.

I participated in FIT in July 2014 and am continuing to work with the program team to add and evaluate new elements. One exciting part of that is putting new teaching tools into the hands of educators. I am currently working on a set of miniature platform microscopes, aka smartphone microscopes. Their design is profoundly simple: a small stage built of wood and plastic, nuts and bolts for adjustments, and a $1.00 low-power lens (adapted from K. Yoshino, Instructables.com). Most cell phone and tablet cameras can be easily positioned on the lens, allowing the user to take photos at 40-175x magnification. These tools can be used by learners of all ages to explore the world of small: seeds, cells, fur, feathers, and much more.

This white fir core shows some years with very little growth, likely due to drought or other environmental stressors. Compare to the 0.5mm pencil lead for scale.

At FIT sessions in 2015, I will use the mini microscopes to feature tree cores from the Sierra Nevada, demonstrating how dendrochronology and technology can be used to facilitate learning. Tree rings are a gateway to understanding our environment, especially the past, present, and future of forests. Each ring records an annual report on a tree’s experience of the forest around it, forming a natural life history. Within each ring, seasonal shifts are marked with changes in cell structure and arrangement, or in the case of a traumatic event like a fire, a scar. Tree ring patterns, often striking and beautiful in their detail, offer approachable visual lessons about how forests work. Educators have already shown interest in using these engaging tools in the classroom: many teachers are enthusiastic about environmental education, but very aware of the limited opportunities for getting their students outside the classroom. My hope is that by providing educators with engaging tools to bring ecosystems into vivid view, we can foster deeper understanding and appreciation of our environment, even if participants never set foot outside the city.