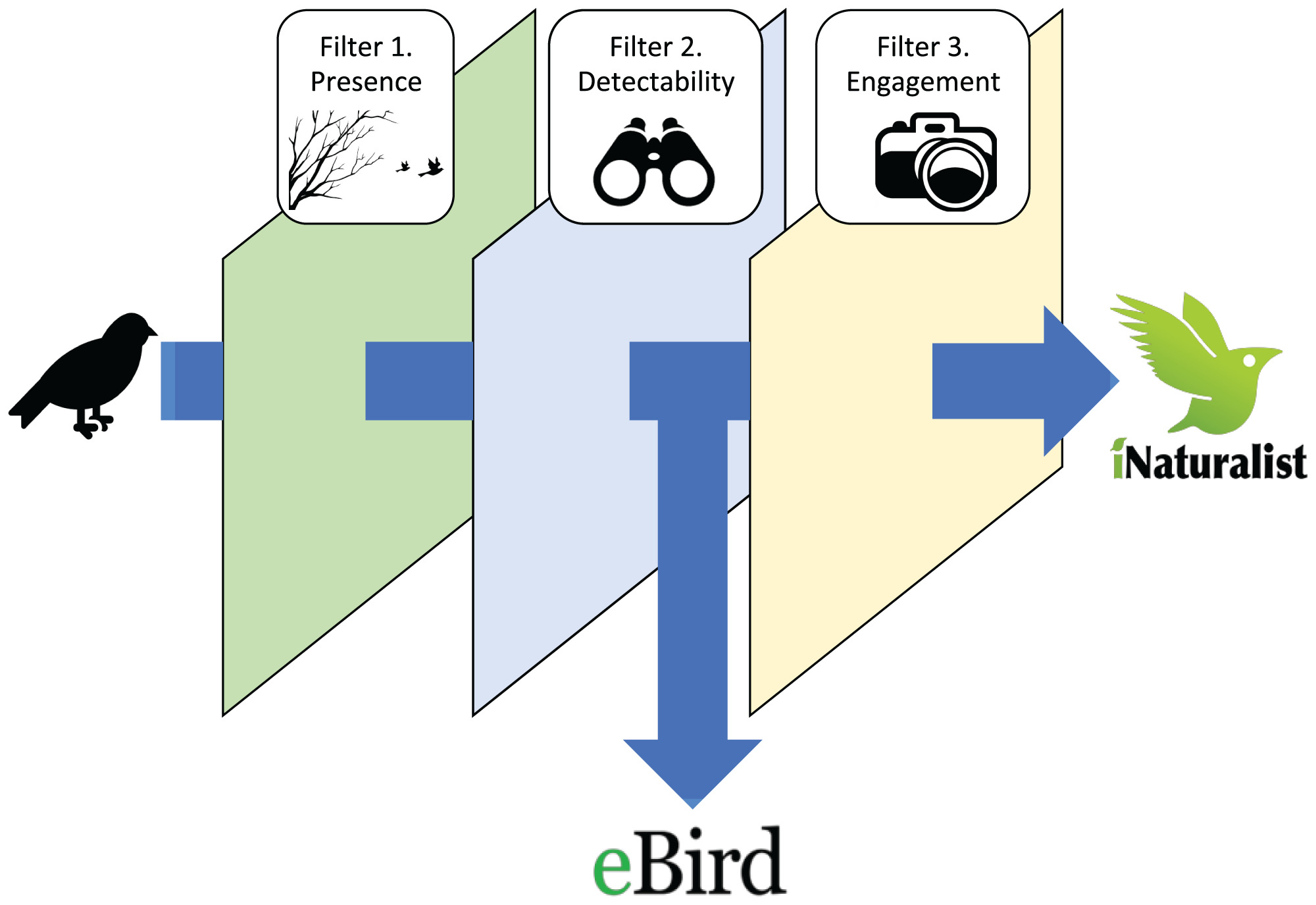

eBird complete checklist observations pass through two conceptual filters: 1) presence and 2) detectability. In iNaturalist, a hypothetical report must pass through an additional filter, 3) engagement, which represents the factors that lead an observer to report one bird over another, encompassing human-driven differences in these data, including the bird’s perceived charisma, the birder’s skill level, logistical obstacles to recording the detection, and spatial sampling effort.

Understanding which bird species drive interaction and engagement on two online citizen science platforms could improve how researchers use complicated biodiversity datasets, according to a new study on birding behavior in the United States.

Published last week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the authors found that iNaturalist and eBird users were more likely to interact with species that are larger, more colorful, or narrowly distributed—traits they say make birds “charismatic” or “engaging.” These findings may also help inform community outreach and conservation efforts.

“Usually we want to get rid of ‘bias’ so we can better understand what is happening to the animals,” said co-author Ben Goldstein, a fourth-year PhD candidate in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management (ESPM). “We tried to flip that in this project. We spend all this time thinking about the ‘bias’ in these datasets. Can we actually study the ‘bias’ itself and identify a pattern that we care about?”

Goldstein and his co-authors looked at data from eBird and iNaturalist, two online platforms where amateur or hobbyist birdwatchers can log their observations. eBird allows users to perform a “complete checklist” when out birdwatching, reporting where, when, and which species they identified. iNaturalist does not offer complete checklists but lets users record their observations—both for birds and other species—through photos or audio clips.

After analyzing the data from each platform, the researchers found that iNaturalist users tend to report species relatively more or less than in eBird complete checklists, revealing different levels of engagement. Large species like the wild turkey, popular species like the burrowing owl, or species with high color contrast like the Indian peafowl were more highly-engaged than others.

“What makes it so interesting to us is that people choose whether or not to engage with these birds,” said Goldstein, who compared the datasets to better understand what motivates people to engage with certain species.

“If we can quantify which species are more engaging, that might be useful for conservation efforts.”

Advocacy and conservation groups can draw on the researchers’ findings to formulate outreach materials that appeal to new naturalists or focus on species that are rarely in the spotlight. In addition, this information can help researchers using this data keep track of what patterns relate to the birds' behavior and which can be attributed more to the birders' behavior.

Perry de Valpine, an ESPM professor of ecological modeling and population ecology, and Sara Stoudt, PhD ’20 Statistics and now a professor of mathematics at Bucknell University, also co-authored the report.

Read the full paper and its findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.